Tumor resection is a medical procedure to eliminate and remove the tissue of a tumor.

WHAT CASES IS IT USED FOR?

Not all cases of brain tumors are apt for aggressive surgical treatment with surgical resection. There are tumors that diffusely infiltrate brain tissue without defined limits, such as many primary brain lymphomas, or diffuse high-grade gliomas, when the affected area of the brain is too large to resect a reasonable proportion of tumor cells, without causing damage that would result in severe neurological deficit.

Other times, the lesion may be somewhat more localized, but it is in a particularly deep, vital area such as the thalamus or the brainstem, which controls involuntary fundamental movements such as breathing, heart rate, blood pressure, digestive processes, etc. In these cases, it is not uncommon to opt for a minimally invasive biopsy in order to offer an alternative treatment such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

In adults, the most frequent brain tumor is due to metastasis, that is, tumors appearing when the cells from a malignant tumor in another organ have traveled through the bloodstream and reached the brain. When the metastases do not exceed two or three in number, depending on the case, surgical treatment may be useful, provided that they are accessible and the risk-benefit ratio is favorable with respect to other types of treatment.

Regarding primary tumors, gliomas or astrocytomas are the most frequent. Grades III and IV are malignant lesions, of which grades IV or Glioblastoma Multiforme are also the most common type and have the worst prognosis.

When the state of the patient and the location of the tumor allow, we will always try to perform at least a partial resection of the tumor to reduce the pressure on the brain, as this pressure is largely responsible for the symptoms the patient is suffering.

With this type of tumor, the best case is always a complete macroscopic resection, since, as a rule, these tumors have isolated malignant cells in microscopic foci that are centimeters away from the apparent limit of the tumor. When these tumors affect both brain hemispheres or clearly affect the structures that connect them, it makes complete resection complicated, since the disease is already affecting both sides of the brain.

Among other types of primary brain tumor, we can find the following:

- Oligodendrogliomas.

- Ependimomas.

- Subependimomas and other variants.

- Neurinomas, which are benign tumors originating from nerves that come directly from the brain, typically from the auditory or vestibulocochlear nerve.

- Tumors originating in vestigial embryonic cells (chordomas, PNET, epidermoid cysts, etc.).

- Others that form in the supporting tissues of the brain such as meninges (meningiomas) or bone (osteomas), which are usually benign, but can sometimes also take on malignant and infiltrating forms.

In the latter types mentioned above, resection is not performed in all cases either. The decision depends on whether the patient has symptoms or if it is a lesion that is growing.

WHAT IS INVOLVED IN THE OPERATION?

Brain surgery normally begins with the process of opening the cranial bone to access the location of the pathology to be treated. This is done by opening a window in the cranial bone, lifting the bone fragment that will be replaced at the end of the surgery (craniotomy) or not (craniectomy), depending on the case and whether the tumor affects the bone in question. If possible, in cases where the bone must be removed at the end of surgery, after the surgeon removes the tumor, the skull will be closed with an implant of a prosthetic cover (cranioplasty).

After lifting the bone we find the dura, the thickest membrane of the three that cover the brain (meninges), which we will also proceed to open to access the brain tissue. In the case of meningiomas, we will look for the area of the meninges where the tumor has its starting point in order to remove it as well, or, if this is not possible given the anatomical location or the high risk of injury to a main cerebral venous vessel, we will at least coagulate the tumor’s base.

In cases of deeper tumors, if the lesion is outside the brain tissue and located in the cerebral ventricles or cisterns that contain cerebrospinal fluid, such as neurinomas, we will be guided by the operating microscope or endoscope until we reach the destination.

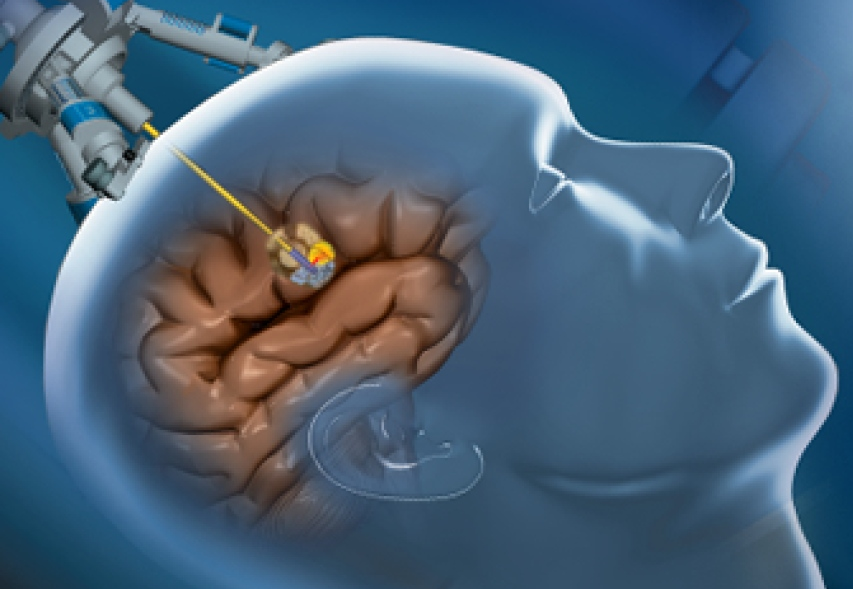

In the case of non-superficial brain tumors, we proceed to corticectomy, which is the opening of the cerebral cortex at a point with little risk of aftereffects. This point has been previously planned and the surgeon’s knowledge of anatomy is essential for this. Some techniques allow technological assistance in this procedure, such as neuronavigation, which allows us to track on screen where we are moving in the brain, serving as a kind of GPS for the surgeon. This is especially useful for locating small and deep lesions.

Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring, in addition to acting as a safety net and alarm system throughout the surgery, allows us, through direct stimulation of the cerebral cortex, to establish whether we are at an eloquent point, especially one affecting voluntary movement. This way, if one spot is too delicate, it allows us to choose a safer entry point a few centimeters away, and all in real time and immediately.

If the risk is acceptable, we will attempt to resect the maximum percentage possible of the tumor. If we know that we are in an area close to a critical area, in addition to the anatomical references, direct stimulation of the brain tissue that we are exposing allows us to evaluate the risk of continuing to remove tissue.

Contrast and fluorescence techniques with compounds such as 5-ALA (Gliolan) are used under the microscope in some cases of high-grade malignant gliomas. At Instituto Clavel have officially certified knowledge for use of these techniques, in combination with the surgical microscope or the exoscope, to optimize the identification and degree of resection of malignant neoplasms.

In addition, sometimes other techniques are used, such as intraoperative brain ultrasound to locate tumors in real time, or endoscopy to access deep and poorly accessible locations.

RECOVERY AND REHABILITATION AFTER TUMOR RESECTION

After intracranial tumor resection surgery, the patient will be transferred to the critical care unit (ICU) for observation, even if he leaves the operating room awake and breathing on his own. This is because the patient’s level of consciousness and neurological state should be carefully monitored during the first 24 hours following surgery.

Once we are sure the patient is recovering correctly, he will be transferred to his hospital room. While in the hospital, the patient will be gradually given a more consistent diet and will be assisted in beginning to move around. Depending on the patient’s previous state and the type and aggressiveness of the surgery, the patient may be perfectly autonomous from the beginning, but in other cases, physical therapy will be used, especially if there is a problem of loss of strength or instability when walking. Typically, patients will need to stay in the hospital 4-5 days before they can safely return home.

Subsequently, all patients will be encouraged to undergo postoperative rehabilitation. In some cases, it will be obvious that the patient needs to recover from a motor deficit of the limbs or even the trunk. But cases with complete mobility can benefit from a rehabilitation aimed at recovering the muscle mass lost during the process.

RISKS OF TUMOR RESECTION SURGERY

In general, it is a surgery with moderate risk, but the risks depend greatly on the type of lesion, its anatomical location, the age and other pathologies of the patient. In most cases, we will achieve a satisfactory tumor resection without negatively affecting the patient’s previous state in any way, and even improving the previous symptoms in many cases. Therefore, most of the complications that we describe do not imply a permanent deficit or after effect.

According to the Spanish Society of Neurosurgery (SENEC), the estimated risks for the surgical treatment of intracerebral lesions are as follows (the range indicates the number given by the most pessimistic and optimistic studies):

- Neurological deficit: varies according to the location of the lesion:

- Hemiparesis (loss of muscle strength in one side of the body): 2 – 12 %

- Changes to vision: 2 – 11 %

- Language disorders: 0,3 – 10 % (depending on the side of the brain affected)

- Sensory (touch) deficit: 0,3 – 10 %

- Internal brain hemorrhage, which can cause neurological deficit or worsen an existing one. 1 – 3 %

- Cerebral edema (inflammation) or stroke (death of cells in the area of the operation): 5 -10 %

- Epileptic seizures after the operation: 1 – 10 %

- Superficial infection of the wound. 0,1 – 7 %

- Deep infection or cerebritis (inflammation of the brain). Osteomyelitis (infection of the bone). Meningitis.

- Death during surgery: 0,5 -3%

Related articles: